|

|

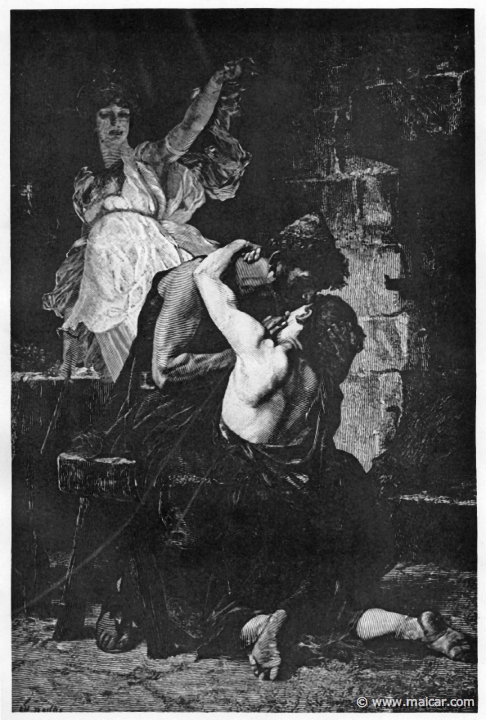

Odysseus sits by the fire as Eumaeus 1 discovers Telemachus at the entrance of his hut. 3511: Eumaeus, Odysseus and Telemachus. Drawing by Bonaventura Genelli, 1798-1868.

|

|

|

"My mother certainly says

I am Odysseus' son; but for myself I cannot

tell. It's a wise child that knows its own

father." (Telemachus to Athena as the Taphian

stranger. Homer,

Odyssey 1.215).

|

|

Telemachus is the Ithacan prince who longed for

his father Odysseus'

return, hoping that it would put an end to the

outrages that were being committed by the SUITORS OF

PENELOPE during his absence.

The time of his birth

Telemachus was born short before the outbreak of

the Trojan War; for he

was still a babe when King Agamemnon's agent Palamedes came to

Ithaca and destroyed his parent's home by forcing Odysseus to comply with

The Oath of Tyndareus,

and join the alliance that sailed against Troy in order to demand, by

force or by persuasion, the restoration of Helen and the Spartan

property that the seducer Paris had stolen.

Odysseus joins the

allies

Odysseus, who did

not wish to become the victim of the oath he

himself had devised, feigned madness in an attempt

to stay at home. But clever Palamedes rightly felt

that he was pretending, and threatening to kill

little Telemachus, forced Odysseus to give up his

pretence, and join the allies. For this reason and

from that time, Odysseus was hostile to Palamedes, and when

later they were fighting at Troy, Odysseus plotted against him, and had him stoned to death by the army as a traitor. Nevertheless, Odysseus had to fight

at Troy for ten years, and

when the war was over he was not able to find his

way home, but instead wandered for another ten

years, coming to places both known and unknown. As

time passed, and neither Odysseus nor his army

returned to Ithaca and Cephallenia, many started to

believe that he was dead.

The SUITORS

That is why a nice collection of youths, coming

from several parts of the island realm, came to his

palace in order to court Queen Penelope, whom they

considered a widow. The fact that the queen could

be, for her age, the mother of any of these youths,

who are known as the SUITORS OF

PENELOPE, did not disturb their minds, which

were filled with the desire of obtaining Odysseus' royal

prerogatives. In addition, these youths did not

conduct their suit from their own homes, but

instead imposed themselves in the palace, consuming Odysseus' estate for

their own sustenance. They argued that Penelope forced them to

act as they did for having fooled them by means of

The Shroud of Laertes, saying that she would marry

once she had finished her work. However, after

three years of wait, they discovered that she

unravelled by night what she wove by day. So, in

order to avoid further cheating, the SUITORS decided

to stay at her home, and undermine the palace's

finances as a way of persuading her to choose one

of them as husband more sooner than later. This is

why Telemachus, who was now about twenty years old,

had reasons to fear his own ruin; for the SUITORS, as he

put it, were eating him out of house and home.

The wrath and sympathy of the gods

But whatever happens on earth has been rehearsed

in heaven. And all this was, as they say, the will

of the gods, or at least of some god; and

particularly that of Poseidon, who was

implacable against Odysseus on account of

his son the Cyclops Polyphemus 2, whom Odysseus blinded at the beginning of his homeward voyage. And since it takes a god to defeat a god or to curb his will, Athena, whose

heart was wrung because of Odysseus' sufferings,

took his defence in the assembly of the gods, and

descended to earth to embolden young Telemachus.

For no one ever reaches maturity whose spirit has

not been instilled by a god or a goddess. And since

the distance between thought and deed is short for

a deity, Athena, having

bound under her feet her golden sandals, was

carried by them in an instant to Odysseus' palace.

The Taphian stranger gives advice

There, having assumed the appearance of a

chieftain from the island of Taphos, which is off

the coast of Acarnania, the western coast of

mainland Greece, she met Telemachus and suggested

him to call the Ithacan lords to assembly, and

there exhort the SUITORS to be

off. Athena also advised

him to sail to Pylos and Sparta, and find out, by

meeting Nestor and Menelaus, whether he

could learn about his father, or by chance pick up

a truthful rumour from heaven. She also made clear

for him his choices, saying that if Odysseus were alive and

on his way back, he could reconcile himself with

the SUITORS'

wastage still for some time. But, the goddess said,

if Odysseus were dead he should build him a funeral mound, and give his mother to a new husband. Yet the goddess advised him to destroy the mob

of the SUITORS who wasted his estate, adding:

"You are no

longer a child: you must put childish thoughts

away." (Athena to

Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 1.296).

These were the instructions that Athena, in the guise of a

Taphian leader supposedly visiting Ithaca, gave to

Telemachus, filling him with daring. One could ask, as Odysseus himself did, why the goddess in her wisdom did not tell Telemachus that his father was alive, instead of arranging a trip to the two Peloponnesian cities. But, as Athena has explained, the adventure was thought to redound to the young man's credit. For the gods will not do what has to be done by men. Yet they appreciate those who are civilized, intelligent, and self-possessed, and these they never desert.

A new heart

Telemachus perceived such a change in his own

state of mind that he realised that a divinity had

been with him; for insight or courage do not appear

in the mind by themselves, but instead are planted

there by the gods. And when the gods leave, insight

and courage leave with them, and that is why Hector 1, who was the

bravest man and the pillar of Troy, was seized by fear

when he confronted Achilles, and ran away

like a fawn. So with this new heart Telemachus summoned the

Ithacan assembly, and there gave the SUITORS formal

notice to quit his palace, exhorting them to feast

elsewhere, or in each other's homes. He also

exposed the details of their main outrages: how

they wasted the palace's wealth in great parties,

enjoying a life free of charge, and how they

pestered Penelope with unwanted attentions. However, the assembly was reluctant to condemn

the SUITORS, the reason being that they were the sons of many a nobleman of the island realm present in the gathering. And since wrong deeds usually look less wrong when perpetrated by sons, cousins, uncles or other lovely relatives, the majority of the assembly found it seemly to keep silent and abstain from disapproving their darling children. And for that, they were themselves blamed by Mentor 4, an old friend

of Odysseus. It was at this meeting that Telemachus declared

that he intended to sail to Pylos and Sparta in order to

inquire after Odysseus'

whereabouts, saying that if he learned that his

father was on his way back he might reconcile

himself to one more year of wastage; but that if he

ascertained that Odysseus was dead he would build him funeral mound, and give his mother to a new husband. However, he also promised to destroy the SUITORS who were

consuming his estate, vouching:

"I will not rest till I have let hell loose upon you …" (Telemachus to the SUITORS. Homer, Odyssey 2.317).

At first the SUITORS, who

were used to rob Telemachus of his best for being

too young to understand, did not believe that he

would ever bring his journey off. Yet, watching his

new attitude, they started to fear that perhaps

Telemachus wished to cut their throats, or

perchance return home from Pylos and Sparta, either with help

or with a deadly poison to pop in the wine-bowl. And these

scenarios like nightmares never fail to appear in

the minds of evil-doers; for evil deeds are both

preceded and followed by evil thoughts.

Even scoundrels want peace

And since no one loves to be hated, the SUITORS entreated Telemachus to leave all thoughts of

violence, and instead take his ease with them and

share a friendly dinner. For even robbers must at

some point love peace and friendship if they ever

are to enjoy the fruits of their crimes. But

Telemachus had had enough of their abuses, and with Athena's help, he put a

ship and a crew in the same place, and sailed away.

Pylos

Telemachus came first to Pylos, which is in

southwestern Peloponnesus, and was there received

by King Nestor, who told

him what he knew about The Returns of the ACHAEAN LEADERS after the war. But knowing very little about Odysseus' fate, Nestor urged Telemachus

to pay Menelaus a visit

at Sparta, for, said Nestor, he had only just

got back from abroad. For this purpose, Nestor put a chariot and

horses at his disposal, and Telemachus traveled

the land route from Pylos to Sparta in two days,

having as charioteer Nestor's son Pisistratus 1, who later became the father of Pisistratus 2, the king of Messenia who was expelled by Temenus 2 and Cresphontes, two of the HERACLIDES.

Sparta

In the evening of the second day, the two young

men arrived to Menelaus' palace, where

they enjoyed the king's hospitality. Menelaus narrated his

own account of The

Returns giving a detailed account of his own

meeting in Egypt with Proteus 2, "The Old Man of the Sea." This god, whom Menelaus had not been

able to catch without the instructions of a

goddess, said the following: that two of the ACHAEAN LEADERS, Agamemnon and Ajax 2, had lost their

lives when they were returning home; but that a

third one, Odysseus,

though still alive, was kept a prisoner in an

island somewhere in the vastness of the sea by the

goddess Calypso 3, who

loved him too much to let him go.

The SUITORS plot against Telemachus

Having heard this, Telemachus made immediate

arrangements for a prompt return to Ithaca,

following the advice that Nestor had given him:

"Don't stray too long from home, nor leave your wealth unguarded with such a set of scoundrels in the place …" (Nestor to

Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 3.314).

That was a sound recommendation. For the SUITORS were

meanwhile alarmed, having realised that Telemachus

had been able to implement the expedition they had

hoped to turn into a farce. And fearing that

Telemachus, who no longer was the child they had

known, would prove to be their bane, they decided

to wait for his ships in the Ithacan straits, and

by killing him put a grim end to his trip in search

of his father. With this criminal purpose in mind,

about twenty of them embarked in full armour,

choosing an appropriate place where to set an

ambush and murder the uncomfortable prince.

Odysseus returns

It may look as a coincidence that Odysseus returned to

Ithaca while Telemachus, who had waited for him in

vain for so long, was away. And yet it often

happens that things start to move simultaneously,

which have long been still. As soon as he landed, Odysseus was informed

by Athena of the

situation at his palace, the goddess of invention

and resource never deserting he who endures with

intelligence and self-possession, and having

together planned the downfall of the SUITORS, she

disguised him, changing his appearance into that of

a beggar.

Strangers and beggars

In his new attire Odysseus went towards

the spot where Athena told him he would meet his most faithful servant, Eumaeus 1, who without

recognising him, offered him hospitality, saying:

"… strangers and beggars all come in Zeus' name." (Eumaeus 1 to the

disguised Odysseus.

Homer, Odyssey 14.56).

That sounds very nice, and yet many know how

strangers and beggars not seldom tell lies and

cheat, more or less as Odysseus himself did in Eumaeus 1's hut. For

not wishing to reveal his identity, he invented all

kind of fantastic tales about his life to touch the

heart of the swineherd Eumaeus 1. Yet no one

should be censured too severely for these tricks.

For as Odysseus himself

said:

"… A tramp's life is the worst thing that anyone can come to. But exile, misfortune, and sorrow, often force a man to put up with its miseries, for his wretched stomach's sake." (Odysseus to Eumaeus 1. Homer, Odyssey 15.344).

Athena urges

Telemachus

In the meantime, Athena informed

Telemachus that it was time to return home. For his

property was unguarded with the SUITORS in his

palace, and his mother's relatives were pressing

her to marry. Besides, said the goddess, Penelope might carry

off some of his things from the house without his

permission; for a woman, the goddess added, likes

to bring riches to the house of the man who marries

her, soon forgetting her former husband and her

children by him.

Understanding hospitality

|

|

Athena watches as Telemachus kisses his father. print008: The meeting between Ulysses and Telemachus. Charles Baude, Engraver.

|

|

Now, as no guest comes and goes as he pleases in

a palace, Telemachus begged Menelaus to give him

leave to return to Ithaca, which the king conceded

without hesitation, being the kind of man who

condemned

"… any host who is either too kind or not kind enough."

which he supported in the fact that

"There should

be moderation in all things, and it is equally

offensive to speed a guest who would like to stay

and to detain one who is anxious to leave."

the rule being:

"Treat a man

well while he is with you, but let him go when he

wishes." (Menelaus to

Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 15.69).

So, Menelaus being a reasonable man in this respect, Telemachus and Pisistratus 1 could immediately leave Sparta. But when they

were near Pylos,

Telemachus asked his friend not to drive him past

his ship, but instead drop him there, thus saving

him from being kept at the palace by Nestor's passion for hospitality. Pisistratus 1 did as Telemachus requested, advising him to embark, at once, that is, before he himself reached home, explaining that:

"My father is

far too obstinate to let you go, but will come down

here himself to fetch you, and I do not see him

going back alone. For whatever your excuse, he will

be very much annoyed." (Pisistratus 1 to Telemachus. Homer, Odyssey 15.209).

Telemachus avoids the ambush

This is how the two young men parted, and

Telemachus sailed away without more ado. On

approaching Ithaca, he, following Athena's instructions,

sailed by night, avoiding the straits where the SUITORS' ship

was lying in ambush. And having landed in the

island at the first point he reached, Telemachus

sent both ship and crew round to the port, while he

himself paid a visit to the swineherd Eumaeus 1, as Athena told him to do.

Telemachus meets his father

At Eumaeus 1's hut

Telemachus met his father, and talked with him

without knowing who he was. But then Athena appeared to Odysseus alone, for as

they say

"… in no wise do the gods appear in manifest presence to all." (Homer, Odyssey 16.160).

and making him come out of the hut, she touched

him with her golden wand, and changed his looks,

restoring his youthful vigour so much that

Telemachus, when he came back, said in awestruck

tone:

"Stranger, you

are not the same now as the man who just went

out." (Telemachus to Odysseus. Homer, Odyssey 16.180).

It was then that Odysseus told

Telemachus the truth, and kissed his son. And from

that moment they started to plan the downfall and

death of the SUITORS, which

came about when Odysseus, having come

to his palace disguised as a beggar, took the bow

that was his own, and shooting at the SUITORS, started

killing them with arrows. A battle then ensued in

the hall of Odysseus'

palace, in which all of the SUITORS were

slain either by Odysseus himself, or

Telemachus, or Eumaeus 1, or Philoetius; for no more than these four

confronted the glad scoundrels, who were more than

one hundred.

Party over

All that happened suddenly, when no thought of

bloodshed had yet entered the heads of the SUITORS. And such a contrast there was between the festive atmosphere and the death of the suitor Antinous 2, who was the first to leave this world with an arrow through his throat, that they thought that the beggar had killed him by accident. Too late did they realise that, except for the swords they were carrying, there were no weapons at hand, for they had been previously removed from the hall by Telemachus. The SUITORS then

made an attempt to negotiate, and promised to make

amends. Yet Odysseus was not in a mood for forgiveness and

reconciliation, and that is why the SUITORS had to

fight for their lives the best they could.

Telemachus' wishes fulfilled

When the battle was over and they were all dead,

Telemachus, following his father's instructions,

took the maids who had slept with the SUITORS, and had

them hanged in the courtyard. And he, along with Eumaeus 1 and Philoetius, also killed the disloyal servant Melanthius 2, who had sided with the SUITORS, after

slicing his nose and ears off, and ripping away his

privy parts as raw meat for the dogs. They were so

angry at him and his lack of loyalty that they also

lopped off his hands and feet. This is how

Telemachus' wishes were fulfilled, for he had said:

"… if men could have anything for the asking, my father's return would be my first choice." (Telemachus to Eumaeus 1. Homer, Odyssey 16.147).

Odysseus' exile

However, some affirm that, because of the killing of the SUITORS OF

PENELOPE, Odysseus was accused of having gone too far. King Neoptolemus of

Epirus, the son of Achilles, was then

called to act as arbiter in the Ithacan civil

conflict, and he condemned Odysseus to exile, and

the SUITORS'

relatives to pay a compensation to Telemachus, who

ruled Ithaca after Odysseus.

Telemachus at Aeaea

It has also been said that Odysseus' son by Circe, Telegonus 3, who had been sent by his mother to find his father, was carried by a storm to Ithaca, where, driven by hunger, began to lay waste the fields. Odysseus and

Telemachus, not knowing who he was, attacked him,

and in the fight Odysseus was killed by Telegonus 3, before they realised who they all were. After this, they say, Telegonus 3, following Athena's instructions,

returned to the island of Aeaea

(Circe's home), taking

with him both Telemachus and Penelope. And they

assert that Athena arranged a double marriage, Telegonus 3 marrying Penelope, and

Telemachus wedding Circe.

|