|

|

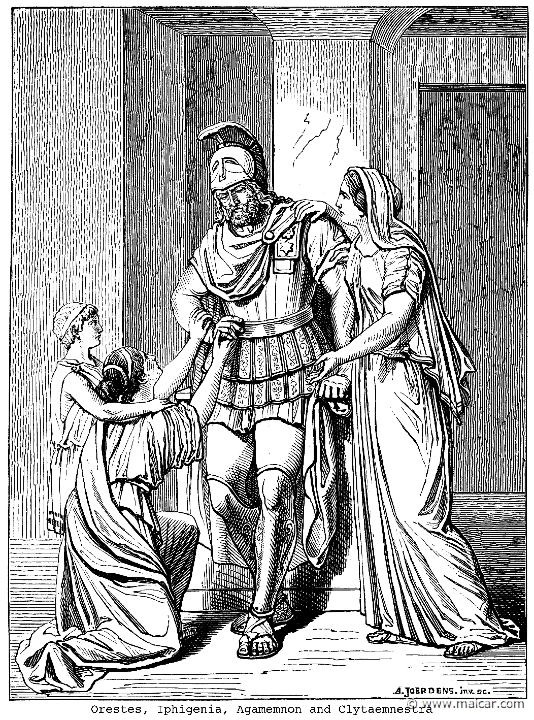

Agamemnon and part of his family: little Orestes 2 is seen close to his sister Iphigenia, who pleads for her life, while Clytaemnestra stands beside her husband. sch001: Agamemnon, Orestes, Iphigenia and Clytaemnestra. Engraving from G. Schwab's Die schönsten Sagen ... 1912.

|

|

King Agamemnon of Mycenae married Clytaemnestra after slaying her former husband and their child. Years later, Agamemnon decided that his and Clytaemnestra's daughter Iphigenia should be sacrificed. Because of this criminal act and other outrages committed against her, Clytaemnestra conspired against the life of her husband and, being helped by her lover Aegisthus, murdered him together with his newly acquired concubine Cassandra. However, Agamemnon's son Orestes 2 took vengeance of his father's murderers, and killed both his mother and her lover.

Birth of Clytaemnestra

They are not few who believe that Clytaemnestra, like her sister Helen, was hatched from an egg brought forth by Leda after consorting with Zeus the swan. But others simply say that of the four babes who were born at the same time, two were the immortal children of Zeus, and two were the mortal children of King Tyndareus of Sparta; for Leda had intercourse with both of them on the same night. And the immortals, they say, are Helen and Polydeuces, whereas the mortals were Clytaemnestra and Castor 1 (for the brothers see DIOSCURI).

Her first husband

Tyndareus gave Clytaemnestra as wife to Tantalus 3, while she still was a virgin. Some have said that Tantalus 3 was the son of Broteas 4, son of Tantalus 1, but others say that he was the son of Thyestes 1. Now, it is also told that all the children of Thyestes 1 were killed by Thyestes 1's brother Atreus as infants, and served as a meal at a banquet. So Tantalus 3 was either not included in the menu that day, or else he was, as some say, son of Broteas 4.

Her second husband

In any case, it was this man whom Clytaemnestra married first. Their marriage, like their child, did not live long; for Agamemnon killed Tantalus 3 and, tearing violently the babe from its mother's breast, dashed it against the stones, breaking its head. This is how Clytaemnestra met the man who became her second husband. It is said that Agamemnon knelt as suppliant to Tyndareus, and that the latter saved his life, allowing him to marry his daughter. But otherwise Tyndareus has not been reported to resent this crime, and he also has been said to have feared that the powerful King Agamemnon of Mycenae might divorce his daughter Clytaemnestra, on the occasion when the SUITORS OF HELEN, competed for the hand of his other daughter. But as Helen married Agamemnon's brother Menelaus, no discontent was expressed for that choice, which was also protected by the famous Oath of Tyndareus.

Powerful brothers

When this second marriage was agreed, the brothers Agamemnon and Menelaus saw themselves in the happy possession of the powerful kingdoms of Mycenae and Sparta, until the seducer Paris arrived from Troy, and disturbed everybody's life by abducting the Spartan Queen, and taking her to that city. Now, the Persians are of the opinion that women are not abducted if they do not want it themselves, and regarding Helen this could be so, if true were that she, years after the destruction of Troy, confessed that she let herself be seduced, as when she said:

"... you Achaeans boldly declared war and took the field against Troy for my sake, shameless creature that I was." (Helen to her husband and visitors. Homer, Odyssey 4.145).

And that was not the first time that Helen had been abducted; for years before Paris seduced her, she was carried off, while still being a very young girl, by King Theseus of Athens. That is why her brothers the DIOSCURI marched against Athens, and having destroyed Aphidnae, took their sister back to Sparta.

Iphigenia

Now Iphigenia is often called daughter of Agamemnon and Clytaemnestra, but there are those who affirm that she was the daughter of Theseus and Helen, then probably only twelve years old, and that on her return to Sparta she entrusted Iphigenia to her sister Clytaemnestra. Iphigenia herself was later, according to some, sacrificed at Aulis, the Boeotian harbor where the Achaean fleet that sailed to Troy in order to demand the restoration of Helen, had gathered. The fleet could not sail because, as the clever seer Calchas discovered, King Agamemnon had offended Artemis while hunting. The remedy for this state of affairs that was upsetting the army with a purposeless wait, Calchas said, was to sacrifice to the goddess the fairest of Agamemnon's daughters, who was Iphigenia. This is how one woman was sacrificed in order to get back another that had been stolen. And although this seemed quite reasonable to those who wished to sail, others, and particularly Clytaemnestra, deemed it to be a great crime, the responsibility of which was Agamemnon's; for it was he who was the commander in chief. Not seldom, those who are about to commit crimes embellish their motivations, arguing that higher aims compel them to do so. In similar manner, they may resort to all kind of lies; for they nurture the curious opinion that noble aims can be achieved through deceit. And so, as Iphigenia was not in Aulis, but instead in Mycenae, Agamemnon sent messengers to bring his daughter to the Boeotian harbor declaring, not that she was to be killed (for the truth would surely keep her away) but that she was to marry Achilles. This is the reason why Clytaemnestra and her daughter Iphigenia came from Mycenae, and appeared very happy at Aulis, believing in their simple minds that their husband and father had arranged a wedding for his daughter. But very soon Clytaemnestra met Achilles in the Achaean camp and he, whose name had become a tool in Agamemnon's subtle scheming, told her plainly:

"I never was a suitor for your daughter, nor have I heard mention of marriage from any son of Atreus." (Achilles to Clytaemnestra. Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis 841).

Soon after a servant revealed the whole truth to Clytaemnestra, telling her also that Agamemnon, having regained his wits, had in fact sent a second message, cancelling the first and bidding them not to come to Aulis. But, as the servant explained, that second message was intercepted by Menelaus, who had understood that the price of his own wife's homecoming was his niece's death. This is how Iphigenia, who had come to Aulis hoping for a husband, was now about to find a slaughterer's knife instead. Clytaemnestra then interceded, and attempted to persuade Agamemnon not to allow such a crime to be committed. For nothing, she said, could console her for the loss of what she called her "sweet flower", nor she could stand to see Iphigenia's bedroom empty, while sitting herself alone in tears, mourning for her daughter, day in, day out. And worst of all, she explained, would be to think that her father, who begot her, had taken her life away. Similarly, Clytaemnestra wondered how she could welcome her husband at home, if he was to become the murderer of their daughter; this is why she also warned and exhorted him:

"In the gods' name, my husband, do not force me to be a disloyal wife to you; nor be disloyal yourself." (Clytaemnestra to Agamemnon. Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis 1184).

And she also wondered how things would look like when the war was over; whether, for example, her husband would then take his children in his arms, as warriors usually do on their homecomings. For that, she thought, would be beyond the right of a man who has murdered one of his children. And if someone should pay with his life, she argued, there could be other, more reasonable alternatives, like casting lots or let Menelaus kill his own daughter Hermione to pay for her mother. But the reason why she herself should pay, Clytaemnestra could not see:

"I am your chaste and faithful wife; yet I must lose my daughter, while the whore Helen can keep her daughter and live safe and flourishing at home in Sparta." (Clytaemnestra to Agamemnon. Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis 1204).

Not only husband and wife debated this issue then; also Iphigenia pleaded for her own life, hoping to touch her father's heart:

"Do not kill me before my time, for it is sweet to look upon the light, and do not force me to gaze at darkness in the world below." (Iphigenia to Agamemnon. Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis 1219).

But nothing moved the commander in chief; for even though he shrank in dread from carrying out this insanity, he dreaded even more to disobey the oracle, Calchas' visions, and the impatience of the army. In fact, even worse evils could come, Agamemnon reasoned, if he did not comply: they would perhaps come to his own palace, and murder him and his whole family. Besides, Agamemnon argued, he was not, as insinuated, Menelaus' slave, but he was slave to Hellas, and therefore he had no power, and was bound to kill his daughter whether he wished or not. What happened next is uncertain; for some have said that Iphigenia was indeed sacrificed, whereas others say that she was saved in the last moment by Artemis, who took her to Tauris (nowadays called Crimea, in the northern coast of the Black Sea). But the outcome, whatever it was, did not change Agamemnon's deed; for in any case, he sent his daughter to be slaughtered at the altar, and Clytaemnestra never forgave her husband's act. And later, after she had murdered him, she remembered:

"... for what Agamemnon did to my sweet flower ... Iphigenia, let him make no great boasts in the halls of Hades, since with death dealt him by the sword he has paid for what he first began." (Clytaemnestra. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1525).

War and discontent at home

After the incident in Aulis, the Achaean fleet sailed to Troy to demand the restoration of Helen and the Spartan property that the seducer Paris had stolen. As negotiations failed, armed hostilities broke out, and the Trojan War began. This was no fast military operation, and it was not before ten years had passed that the city could be taken. Now, longer conflicts imply greater risks, in particular for those who are fighting abroad; for, among many other things, discontent might spread at home. Some have said that Palamedes' father Nauplius 1, on account of the crime committed against his son during the war, instigated sedition in many Achaean cities by inducing the wives of the ACHAEAN LEADERS to take lovers while their husbands wasted themselves in the Trojan siege. So just as Diomedes 2's wife Aegialia slept with Cometes 2, and Idomeneus 1's wife Meda 2 took Leucus 1 as lover, Clytaemnestra let Aegisthus, not only enter her bed, but also sit on the throne of Mycenae. Aegisthus was by no means a newcomer; for he had, years before, murdered his cousin Agamemnon's father Atreus, extending the chain of crimes which tormented the family of the Pelopides, since the Curse of Myrtilus. Aegisthus had then his own dynastic reasons. For both Atreus and Thyestes 1, fathers of Agamemnon and Aegisthus respectively, wishing to sit on the throne of Mycenae, performed horrible deeds against each other, their heirs inheriting the rivalry. Agamemnon had left in Mycenae a minstrel to guard his wife during his absence, but Aegisthus took him to a desert isle and left him to be the prey and spoil of birds, and himself seized both throne and queen.

Clytaemnestra's feelings for Iphigenia and Orestes 2

This is the course that Clytaemnestra took after the Aulis incident. Yet she never felt for her son Orestes 2 the same devotion she had showed for her sweet flower Iphigenia. For when Aegisthus seized power in Mycenae, he, being naturally hostile towards Agamemnon's descendants, would have probably murdered the little prince Orestes 2, had he not been smuggled out of the country to be raised by Strophius 1 in Phocis, the region bordering the Gulf of Corinth west of Boeotia.

No crown but sword

When after the sack of Troy, Agamemnon became the great victor of his age, neither the Aulis incident and what happened to Iphigenia more than ten years before nor his wife's state of mind worried him. And, as if he thought that he could pile any number of outrages on his wife, he appeared in Mycenae accompanied by Cassandra, whom he had taken as a concubine. But Agamemnon never enjoyed his triumph. For Clytaemnestra had already planned, together with her new sweetheart Aegisthus, to welcome her husband not, as they say, with crown or garland but with a two-edged sword. And so, unaware of what was waiting at home, Agamemnon met sedition and death in the shape of his wife and her lover. Such was the end of this powerful king, who conquered Troy and many other cities, but was defeated by adultery, finding death in his own palace. Agamemnon's arrival was known beforehand by Clytaemnestra and her lover; for a succession of beacon-fires had been arranged to flash the news from Troy, so that they should know when the city was captured, and the king was about to return. So after the fall of Troy, Clytaemnestra kindled altar-fires throughout the city, feigning celebration, and when Agamemnon arrived, he, having walked on dark red tapestries into the palace, was slain either by Clytaemnestra, or by Aegisthus, or by both. But on receiving her husband Clytaemnestra sounded as a loving wife, making moving speeches for the ears of Agamemnon, and the Elders of the city:

"... when a woman sits at home and the man is gone, the loneliness is terrible ..." (Clytaemnestra to Agamemnon and the Elders. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 848).

She also made excuses to explain the absence in the reception of the crown prince Orestes 2:

"You risk all on the wars—and what if the people rise up howling for the king, and anarchy should dash our plans?" (Clytaemnestra to Agamemnon. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 872).

Agamemnon trapped

And reaching towards his chariot she whispered sweet words:

"Come to me now, my dearest, down from the car of war, but never set the foot that stamped out Troy on earth again, my great one." (Clytaemnestra to Agamemnon. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 898).

And having heard their mistress, the attendants spread the crimson tapestries between Agamemnon and the entrance of the palace. That was the king's last walk; for as soon as he came inside the palace he was murdered. When Agamemnon was dead, his murderers put his body on a silver cauldron shrouded in bloody robes with the body of his concubine Cassandra, whom they also slew, lying beside him. And when they had thus arranged the corpses, Clytaemnestra revealed them to the Elders of the city; for these deeds cannot be kept secret, yet they have to be justified, and that is why she proudly and publicly declared:

"Here is Agamemnon, my husband made a corpse by this right hand—a masterpiece of Justice. Done is done." (Clytaemnestra to the Elders. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1429).

When the Elders heard this avowal, they threatened the queen with exile. But then Clytaemnestra rebuked them for not having reacted when the king sacrificed his own child, while Aegisthus emerged from the palace with his bodyguard, enjoying what was also for him a brilliant day for vengeance. Seeing now clearly what was going on, the Elders were on the point of coming to blows with Aegisthus and his bodyguard, but Clytaemnestra restrained them all:

"No more, my dearest ... No bloodshed now. Elders, turn for home before you act and suffer for it ..." (Clytaemnestra to Aegisthus and the Elders. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1690).

Aegisthus, master of Mycenae

This is how Clytaemnestra found revenge, and Aegisthus seized power in Mycenae. Yet the gods had warned him not to slay the king nor woo his wife; for from Orestes 2, the prince in exile, should come vengeance for Agamemnon. Also the Elders reminded him of Orestes 2, but Aegisthus would not listen:

"Exiles feed on hope—well I know." (Aegisthus to the Elders. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1703).

And so, having become the master, Aegisthus rejoiced at his power and reigned in Mycenae for seven years, and when he was drunk, they say, he used to jump on Agamemnon's grave shouting insults against the dead king and his children.

Clytaemnestra's children

Orestes 2 was in Phocis, but her sister Electra 2 stayed at home, and although she had many suitors, she was at first prevented by Aegisthus to marry a prince; for he feared that her son would revenge Agamemnon's death. Later, as Aegisthus also feared that she might bear a son in secret to a man of noble blood, he planned to put an end to his apprehensions by killing her. Clytaemnestra then, fearing the hatred that such a deed would arouse, intervened in favor of her daughter, and Aegisthus conceived instead the idea of marrying Electra 2 to an insignificant man. For, he reasoned, a nobody would not go stirring up old blood, asking that the debt for Agamemnon's death should be paid. Clytaemnestra agreed to this arrangement, for, as it is said, women's love is for their lovers, not their children. Yet others say that Electra 2 did not marry, and never ceasing to mourn her father, waited at home for her brother Orestes 2 to return.

|

|

The ERINYES of Clytaemnestra pursue Orestes 2. Beside Athena, who presides the court, sits Apollo. sch481: Orestes at trial. Engraving from G. Schwab's Die schönsten Sagen ... 1912.

|

|

Return of Orestes 2

Seven years after the death of Agamemnon, his son Orestes 2, who now was grown up, went to Delphi and asked the oracle whether he should avenge his father's death. And as the oracle of Apollo told him that he should, he departed secretly to Mycenae together with his loyal friend Pylades, the son of Strophius 1. What exactly happened when Orestes 2 came to Mycenae (see Orestes 2) has been differently told. But all accounts declare that Orestes 2, on his arrival to Mycenae, performed a most terrible deed. For he not only slew Aegisthus, who was, as he saw it, usurping his royal rights, but he also murdered his own mother Clytaemnestra, despite her prayers and warnings. This is how she begged for her life:

"Wait son! Have pity, child, upon this breast, which you held, drowsing away the hours, sucking, with toothless gums, the milk that nourished you ... I gave you life. Let me grow old with you." (Clytaemnestra to Orestes 2. Aeschylus, Libation-Bearers 895).

and this is how she warned him:

"You have no fear of a mother's curse, my son? ... Watch out, the hounds of a mother's curse will hunt you down." (Clytaemnestra to Orestes 2. Aeschylus, Libation-Bearers 923).

Yet nothing could stop this son who, feeling compelled to avenge his father by shedding his mother's blood, stabbed her to death. Now, it is widely known that murderers, once they have committed their deed, pay a very high price for it; for they seldom are able to recover that inner quality which goes under the name of "peace of mind", and consequently they usually ruin their own lives. And few things are more terrible than having parted with serenity; for both vigil and sleep are a torment when consolation refuses to give any assistance. This is why Orestes 2, after committing his crime, went, as they say, "mad", a term which does not necessarily mean "completely stupid", but rather describes a soul under harsh torture. And so Orestes 2 became a prostrated man, spending most of his time in bed as if he were wasted with a fierce disease. This is the work of the ERINYES, who persecuting and lashing the murderer, turn painful remorse into the master of both heart and mind, destroying both by grief, and thereby provoking insane fits.

Clytaemnestra seeks revenge after death

For some, as it appears, life does not end when the flesh is destroyed. So was at least for Clytaemnestra; for after death she still wished revenge, this time against her son. And not little was her disappointment when her ghost caught the ERINYES asleep, granting a truce to their victim Orestes 2, instead of tormenting him without interruptions. But no one can escape the nature of things, and even the ERINYES, wearied with their pursuits, must, at some point, give way to Sleep, himself a powerful god. Yet Clytaemnestra woke them up, inciting them against her son:

"Let no fatigue overmaster you, nor let slumber so soften you as to forget my wrong...Waft upon him your bloody breath, shrivel him with the fiery vapour from your vitals, on after him, wither him with fresh pursuit." (Clytaemnestra to the ERINYES. Aeschylus, Eumenides 135).

But Orestes 2, having Apollo as advocate, was tried for homicide in Athens in a court presided by Athena, and acquitted. Nothing else has been known about Clytaemnestra ever since, and not even those who descended to the Underworld, as Odysseus and Aeneas, have reported anything about her.

|