| Homeric and Post-Homeric War Leadership |

|

Epic poetry, we are told, was composed in early times, being first chanted by minstrels throughout the so-called “Dark Age” of Hellas (before the 9th century BC) and later written down during the Archaic period (from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Hellenic literature, preceding lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, and mythography. The main concern of this ancient form of expression is war. Therefore the term epic (derived from épos, word, song) is applied to narrative poems describing the deeds and vicissitudes of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction which frequently affects mankind.

|

|

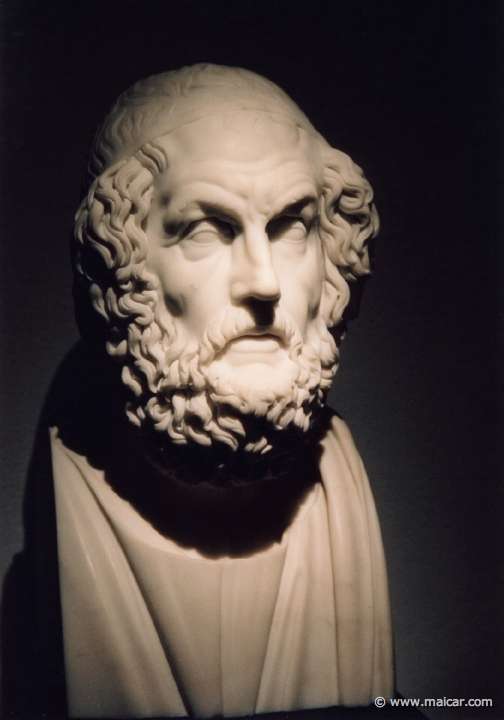

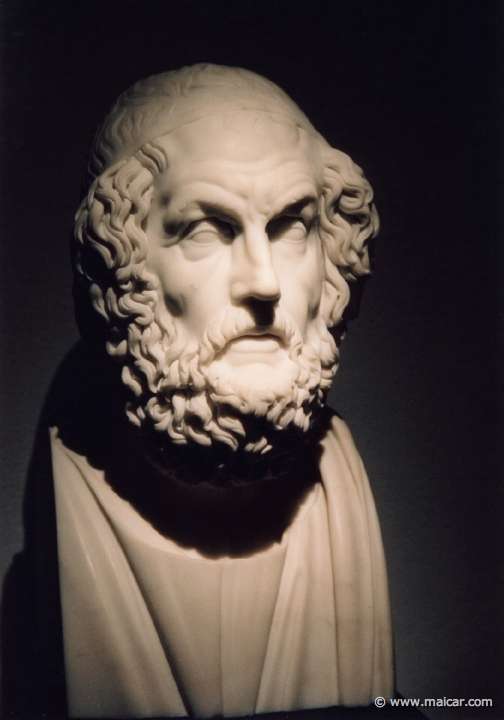

Homer | 9301: Bertel Thorvaldsen 1770-1844: Homer. Copy of an antique bust, 1799. The Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen.

|

Sometimes the word cycle is used (from kúklos, circle) to refer to any group of poems, tales or plays revolving about a central theme. And since what we call Epic Cycle (epikòs kúklos) narrates the legends of the Theban and Trojan wars, we may then speak of a “Theban Cycle” and a “Trojan Cycle.” The Epic Cycle is sometimes called Epic Fragments since only scraps remain of the original works. Some of the poems belonging to the Trojan Cycle narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), others those which took place during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium), and yet others describe events that happened after the war (Returns and Telegony).

The phrase Cyclic poems conventionally excludes both the Iliad and the Odyssey, but if these two works were included, we would then get a material divided into what Tzetzes called “Antehomerica” (i.e., before the war), “Homerica” (during the war), and “Posthomerica” (after the war). Such a division honors one author (Homer), but must paradoxically place one of the two works attributed to him (the Odyssey) under the heading “Posthomerica,” which of course looks rather odd. In another context, Posthomerica is also the Latin title of the poem by Quintus of Smyrna (5th century), who, having picked up the story where the Iliad ends, narrates the fall of Troy in detail.

The expression post-Homeric may simply refer to authors, objects, traditions, or myths that come after Homer, who possibly lived (if not regarded as a fictitious person) around the 9th century BC: “I suppose Hesiod and Homer flourished not more than four hundred years earlier than I,” writes Herodotus. Yet Homer himself may be regarded as post-Homeric, since we would rather call “Homeric” not the poet’s own time but the one described in his songs: the Bronze Age of Hellas, when Troy is supposed to have fallen—around 1200 BC, according to tradition. (Incidentally, the historical “Bronze Age” should not be confused with the Age, or race, of Bronze described by Hesiod in his Works and Days, and by other authors.)

The adjective Homeric may also be employed figuratively, to denote something grand in scale—whether battles or journeys—where the courage and exploits of heroes are destined to play a certain role. Under the conditions of war, destined means, foremost, confronting death. When engaging in war, a man may die or else save his life. But whereas preserving one’s life not necessarily is a matter of Fate, dying always is. In Homeric epics (and in the myths in general), Fate presides over the unavoidable departure from this world and over the circumstances leading to it as well. War, in turn, produces the prolific playground where such circumstances multiply.

Innumerable deaths have been reported in the battlefield of Troy. A sword on the head, in the neck, in the stomach, in the liver … A spear in the back, in the gut, in the chest, in the jaw, in the mouth, in the eye, in the groin, in the ribs, through the cheek … An arrow in the buttock, in the back of the neck … A rock on the head …

To be sure, those examples are “Homeric”: we have read them in the Iliad. Yet today we are not particularly interested in them. Instead, we will focus on who are participating in that deadly process, meaning by “who” the rank of the warriors, rather than their names.

Fortunately, such an investigation requires no great effort. To be sure, what we wish to demonstrate is in plain view. We may therefore dispense with any tedious gathering of numerical data and its subsequent submission to statistical analysis and interpretation, and limit ourselves to picking a few examples. And since examples abound (both in the Homeric catalogue of forces as well as in other sources), the first that come to mind will do:

The supreme leader of Troy was King Priam, but since he was no longer young the commander of the Trojan forces was his son—the crown prince Hector—later remembered as “the pillar of Troy” (Pindar) for his efforts and courage in the battlefield.

“Trojans” are called those who were under the sway of Priam when the war broke out, whether citizens of Troy or not. For example, King Mynes of Lyrnessus (a city east of Mount Ida), King Eetion of Thebe, King Altes of the Lelegians, the Dardanians (represented by Aeneas), or King Asius of Phrygia were all “Trojans,” as also was Pandarus, who represented the dynasty of Zelia (a place “beneath the nethermost foot of Ida”) and is remembered for having broken a truce by shooting an arrow at Menelaus. The death of Altes has not been reported, but both Mynes and Eetion were killed by Achilles, and Asius by King Idomeneus of Crete.

On the Achaean side, Agamemnon—King of Mycenae and Commander in Chief of the coalition that sailed against Troy—personally killed more than a dozen warriors: two sons of Priam (Isus and Antiphus), as well as several high-ranked men (among which Odius, Deicoon, Adrastus, Amphius, Bienor, Pisander, Hippolochus, Iphidamas). Agamemnon was wounded in battle by Coon, son of a prominent Trojan (Antenor). Agamemnon’s brother—Menelaus, King of Sparta—shows a similar record, having wounded Helenus (son of King Priam) and killed several noteworthy men.

These examples are here merely to highlight a salient feature of the Homeric battlefield, namely the conspicuous presence in it of kings, princes, and other wealthy or influential men.

Now, in the course of the innumerable wars that visited humanity since the fall of Troy, battles continued to be “Homeric” in this particular sense. For more than three thousand years, rulers and field-marshals kept the habit or disposition of risking their own lives in the battlefield. In this regard, the historical record is as overwhelming as the Iliad. In the brief survey that follows, the term “Homeric” is used in this simple sense: “presence of rulers or prominent men in the battlefield in ways similar to those observed in the Iliad.”

As a first example, taken from Classical times, we may choose King Leonidas, dead at Thermopylae in 480 BC. Later, at Cunaxa (401 BC), King Artaxerxes defended his throne against his brother Cyrus, who managed to rout the king’s bodyguard before being struck down while personally pursuing his brother. Both Philip II and Alexander (king and heir) were present at Chaeronea (338 BC), the father leading the hypaspists, and the son the cavalry. Alexander was later wounded at Issus (333 BC) and also at the Phoenician city of Gaza. Alexander’s uncle, ruler of Epirus, died in an Italian battlefield, as also did King Archidamus III of Sparta.

These are Homeric examples also in the sense that those strategoi were not merely observing the military operations from some protected hill at the rear.

Cleopatra, historians tell us, “lost her nerve” at the naval clash of Actium (31 BC) and withdrew her ships. Perhaps, but on the other hand we will have to admit that she had the Homeric nerve to show up! That day her lover Antony (former triumvir) soon followed her in her flight, leaving most of his fleet behind in a state of leaderless confusion. Also Antony’s hasty departure has been criticized, but we also learn that some time before that battle he had invited his enemy to settle their differences in single combat, which Octavian (later called Augustus) refused. To be sure, single combat is also a Homeric possibility: Hector met Ajax, and later Achilles. And Paris and Menelaus were meant to settle with a duel the outcome of a war that had already lasted ten years.

The Homeric leadership continued without interruption, and three centuries after Actium (in AD 363) the Emperor Julian perished as a result of a wound inflicted during an unimportant skirmish … Time runs … In 1199, Richard Coeur de Lion was killed by a crossbow bolt while besieging the castle of Châlus. And Richard III of England (to whom Shakespeare attributed the famous utterance, My kingdom for a horse!) perished at the battle of Bosworth (1485). And during the Thirty Years War, Gustav II Adolf of Sweden lost his life at Lützen (1632). Napoleon I, we learn, was wounded in battle, perhaps more than once. And the second Napoleon, called the third, found himself among the prisoners when the Prussians defeated him at Sedan, in 1870. On the same year, in the battle of Cerro Corá by the river Aquidabán (a last stand in the War of the Triple Alliance), both the President of Paraguay—Solano López—and the Vicepresident lost their lives.

From the second half of the 19th century, however, rulers began disappearing from the battlefield, being soon followed, in their quiet flight, by field-marshals and generals. Here we are not concerned with the reasons behind this flight—whether they are of a moral nature or were induced by democracy, industrialization, the introduction of mechanized warfare, longer chains of command, or by something else. We are merely observing that from at least c. 1200 BC to c. AD 1900 (3100 years) there existed a “Homeric war leadership,” that is, a conspicuous presence of rulers and other prominent men in the battlefield, and that c. 1900 a new “post-Homeric era” started, defined by their equally conspicuous absence from the battlefield.

Thus a three millennia-long tradition was discarded only about a century ago when rulers and other prominent personalities finally deserted the battlefield, showing no intention to return to it. As it seems, this desertion was completed in the course of just a few decades, though it would be possible to argue that it was long heralded by the figure of a well protected field-marshal keeping an eye on the battlefield from a distant hill. Whether it is a matter of decades or of a longer period, we should nevertheless call it “gradual desertion” to distinguish it from the precipitous one—“sudden desertion”—which is accomplished while a certain battle is still being fought.

Deserting the battlefield suddenly (as Antony and Cleopatra did at Actium, or Darius III at Gaugamela in 331 BC) seriously undermined authority and the willingness to fight of both troops and lower commanders. But apparently, the gradual desertion (completed in the course of, say, three generations), has had none or very little effect on the willingness to fight, and it also passes almost unnoticed to the point that practically no one wonders—whether in the heat of the fight or else watching events at home through some electronic device—where all rulers and field-marshals of the past have gone.

And yet, for the slumbering awareness of the post-Homeric era, a general may still become “a legend.” No longer for facing the enemy eye to eye, though. But for exercising some sort of self-discipline, or for leading what the post-Homeric era regards as an ascetic life: sleeping fewer hours, jogging every morning, eating frugally, or being willing to check all details in every report.

Carlos Parada

Lund, summer 2010

written for the Hellenic electronic magazine Ideón Ántron

|