|

|

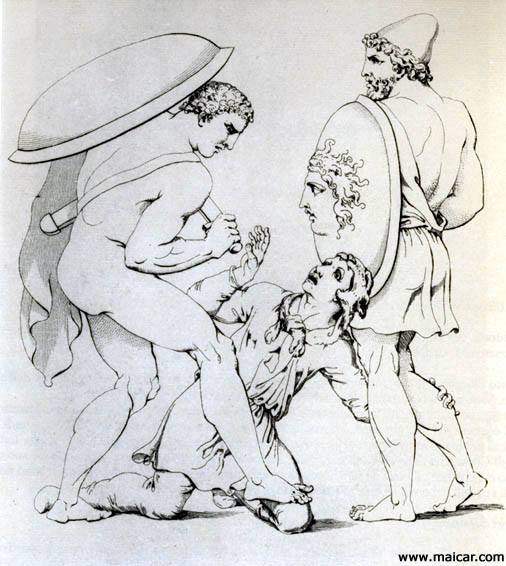

J. H. W. Tischbein, 1751-1829: Diomedes and Odysseus capture Dolon, the man who disclosed the whereabouts of Rhesus.

|

|

|

"No man of knightly soul would deign by stealth to slay his foe; he meets him face to face. This man who skulks, you say, like a thief, and weaves his plots, him will I take alive, and at your gates' outgoings set him up impaled, a feast for vultures …" (Rhesus 2 to Hector 1. Euripides,

Rhesus 510).

|

|

Rhesus 2 is chiefly remembered because he came from Thrace to defend Troy with great pomp and circumstance, but died on the

night of his arrival, without ever engaging in

battle.

The Trojans camp in the plain

In the tenth year of the Trojan War, the nereid

Thetis kissed Zeus' knees

and touched his chin, begging him to avenge her son Achilles, whom Agamemnon had

outraged. And while Achilles, nurturing his

wrath, refused to fight, the god, listening to her

prayers, acquainted the Achaeans with defeat, so

that they would learn to honour him that so often

had brought them victory. This is why Hector 1, the pillar of Troy, could make fierce

attacks against the wall and ditch that the

Achaeans had built to protect themselves,

threatening to destroy their camp and their ships. And so Hector 1,

after a victorious day, besieged the besiegers, and

the Trojans did not seek refuge within the walls,

but instead camped outside the city, midway between

the enemy ships and the river Scamander. And when

night came, they lit innumerable fires through the

plain producing an impressive sight, and round each

one sat fifty men with their horses and chariots

beside them, waiting for Dawn to renew their attack.

Agamemnon cannot

sleep

In the meantime, Agamemnon could not

snatch a moment's sleep, having glanced from the

Achaean camp at the enemy plain with its many fires

burning. For he feared that after ten years of

efforts the whole expedition would end in disaster.

And since a sleepless king means a sleepless court,

several commanders were woken up to discuss the

situation; for the enemy was sitting close, and the

Trojan plans being unknown, even a night attack

could be feared.

Hector 1's temerity

These movements were perceived by the Trojans,

who from the plain noticed the torches going back

and forth. When Hector 1 was informed of the activity in the Achaean camp,

he supposed that the Achaeans, after suffering

defeat the day before, had decided to return to

Hellas. And believing that their escape deprived

him of his final victory, he lamented:

"Ah Fortune,

that you should in triumph's hour rob of his prey

the lion, before my spear with one swoop make and

end of Argos' host!" (Hector 1.

Euripides, Rhesus 56).

Such was Hector 1's

self-confidence at the time when Zeus, not for his but for Achilles' sake, let him

be victorious.

Aeneas speaks for moderation

Assuming then that the lights moving in the

enemy camp meant that the Achaeans were boarding

the ships in panic, he wished to attack them, and

by preventing their flight, catch the elusive

victory. But his intent was stopped by Aeneas, who admonished

him:

"Would that

your prudence matched your might of hand! So is it:

one man cannot be all-wise, but diverse gifts to

diverse men belong—prowess to you, to others

prudent counsel." (Aeneas to Hector 1. Euripides, Rhesus 105).

There was no reason, continued Aeneas, to deduce from

the fires that the enemy was fleeing. Nor was it

wise, he added, to lead the host over the trenches

in the hush of night, perhaps to find that the

enemy was not in the act of fleeing, but waiting

and well prepared to make a stand. Since others shared Aeneas' opinion, Hector 1 resolved to send a spy to find out which stratagems, if any, the Achaeans were conceiving. It was then that Dolon 1 volunteered to help, and consented to risk his life, as he put it, for the sake of his country. Yet not without a reward; for as he explained:

"… all work that has reward in prospect, is with double pleasure wrought" (Dolon 1 to Hector 1. Euripides, Rhesus 162).

This was no difficulty, since Hector 1, as it appears, was a generous man, ready to share many things, except his royal power. The exception did not pose a difficulty to Dolon 1 either, who clearly stated that he was not interested in carrying the burden of royalty. He also refused to be taken, through marriage, into the royal family, and likewise he rejected gold, since he was son of the sacred herald Eumelus 3, a rich man. And when Hector 1's other guesses also failed, Dolon 1 revealed that he would consent if he were presented, after victory, with the immortal horses of Achilles, which once Poseidon had given to Peleus.

Hector 1 replied with

an oath:

"Let Zeus himself … hear me swear that no other Trojan shall ride behind those horses, and that you shall rejoice in them for the rest of your days." (Hector 1 to Dolon 1. Homer, Iliad 10.329).

This was the agreement; and cherishing both promise and prospect in his heart, Dolon 1 went on his mission, disappearing into the evil night.

The Achaean spies

In the meantime, similar thoughts occupied the minds of the assembled Achaean commanders, who deemed it opportune to send someone to spy the Trojans, on the chance of overhearing some talk about their plans. And after offering the rewards they judged appropriate (or perhaps only those rewards that could be afforded, since they were not as great as that promised to Dolon 1), Odysseus and Diomedes 2 were

appointed to steal into the Trojan camp.

Arrival of Rhesus 2

It was approximately at this time, on this fatal night, that Rhesus 2, king of Thrace, having crossed the Hellespont with a host, appeared in the plain, purposing to assist the city that so many times before had entreated him to come to its help. Wearing a magnificent golden armour, and driving a chariot beautifully finished with gold and silver, drawn by horses whiter than snow, Rhesus 2 was a fantastic sight. And to let his arrival gain even more splendor, he declared that already the day after he would storm the enemy camp, and falling upon the fleet, he would slay the Achaeans. And for that prowess, he asserted, no one else was needed except himself and his Thracians.

Reproaches

Allies are almost always welcome. Yet Hector 1 did not receive

this golden-mailed commander with an open heart.

For feeling that victory was at hand, he thought

that the Thracian had arrived for the feast rather

than for the fight. He therefore reproached him his

late arrival, saying:

"Long, long since should you have come to aid this land …"

and

"You cannot say that you did not come to your friends, nor visited them, for lack of bidding. What Trojan herald, or what embassy came not with instant prayer for help …? What splendour of gifts did we not send to you?" (Hector 1 to Rhesus 2. Euripides, Rhesus 396ff.).

This said, Hector 1 also reminded him of how he in the past had come to Thrace to help Rhesus 2 get rid of his enemies, thus securing the Thracian kingdom for him.

Boasts

But as Hector 1 soon

learned, this man had simply been too busy, and as

vexed as anyone else on account of his own absence.

For each time he had wished, during the last ten

years, to march to Troy,

the Scythians, he

explained, had fallen upon his kingdom. But now,

having defeated them, taken hostages, imposed

tribute, and so on, he was finally at Troy; and although his

coming was late, he said, it was nevertheless

timely, since Hector 1, in ten years, had achieved nothing. By way of contrast, he now purposed to defeat the Achaeans in one battle, and besides march afterwards against Hellas, and destroy it for all time to come. When they had thus exchanged enough boasts and

reproaches, Hector 1 assigned a place to encamp and rest to Rhesus 2 and his troops.

The spies meet

In the meanwhile, Odysseus and Diomedes 2,

conveniently equipped for their mission, left the

Achaean camp, picking their way among the dead of

the last day's battle. Soon, as they went through

the darkness of night, they discovered a man coming

towards them, and having hidden among the dead

beside the path, they let him pass and go a little

way, before they pounced on him from behind.

Dolon 1

On hearing footsteps behind him, Dolon 1 (for that was the man) stopped, since these could be Trojans, perhaps bringing him a message from the camp. But when the other two came closer, he knew them for enemies and started to run as fast as he could, although in the wrong direction. As he came closer to the Achaean outposts, Diomedes 2 reached him, threatening him with his spear, and Dolon 1 came to a halt pale with fear and with his teeth chattering in his mouth. When his pursuers gripped his arms, Dolon 1 burst into tears, begging to be taken alive, and promising to ransom himself with the bronze and gold that his father would gladly pay, on learning that his son had been made a prisoner. Odysseus replied by exhorting him to pull himself together, and not be troubled by the thought of death. And then he let a rain of questions fall on Dolon 1: on his reason to leave his camp, on the whereabouts of his commander in chief, on the position of the Trojan sentries, on the Trojan plans, and on the places where everybody was sleeping. Dolon 1, for whom life was now more precious than Achilles' immortal

horses, did pull himself together in his own way,

and answered truthfully all the questions, telling

that Hector 1 had sent him, revealing where this same commander now was, how the guards kept a lookout, in which parts of the camp the allies of the Trojans were sleeping, and which the positions were of the Carians, the Mysians, the Phrygians, the Lycians, and several others. And Dolon 1's fear make him so helpful that he even came with proposals:

"If your idea is to raid our positions, what about the Thracians, newcomers, on their own, at the very end of the line? Rhesus, their king … is with them. That man has the loveliest and biggest horses I have ever seen. They are whiter than snow and they run like the wind. And his chariot is cunningly wrought with gold and silver, and he brought a huge armour of gold with him too, a wonderful sight." (Dolon 1 to Odysseus.

Homer, Iliad 10.435).

Having truthfully revealed all these excellent things, Dolon 1 expected to be taken as a prisoner to the ships, or to be tied up, while the other two found out whether he had told them the truth or not. But Diomedes 2, having decided not to let the man ever be a nuisance again, fell on him with his sword, just as Dolon 1 was about to plead for mercy, and cut off his head, which, as they say, met the dust before it ceased to speak. Such was the end of Dolon 1.

The Thracian encampment

|

|

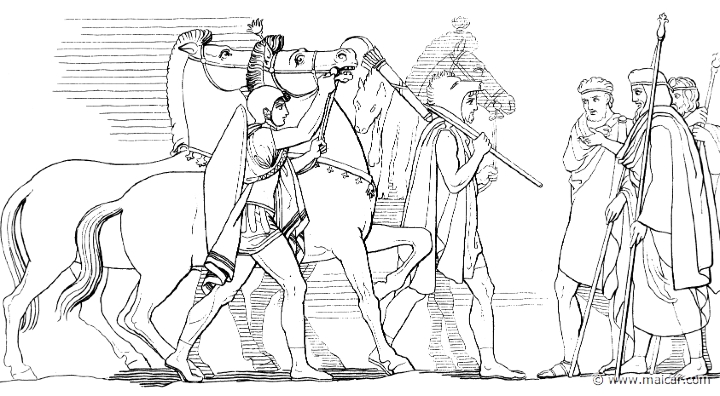

After Rhesus' death. Present: Diomedes, Odysseus, Nestor. | il203flax: "And the horseman, Nestor of Gerenia, was first to question them: 'Come tell me now, Odysseus, greatly to be praised, great glory of the Achaeans, how you both took these horses. Was it by entering the throng of the Trojans? Or did some god that met you give you them? Wondrous like are they to rays of the sun.'" (Hom.Il.10.545). John Flaxman (1755 – 1826).

|

|

Now Odysseus and Diomedes 2 went ahead through the night, the arms, and the dead, coming soon to the Thracian encampment, where they found the equipment neatly piled and the men asleep, with a pair of horses beside each one of them. Soon they discovered the horses whiter than snow; and they knew that the man beside them, breathing heavily under the influence of evil dreams (as they say), was Rhesus 2.

The carnage

In the silence of the night, the two saboteurs

quickly divided the tasks among them; and while Diomedes 2 killed the

men with his sword, Odysseus dragged aside the bodies, so that the horses might easily pass and not be frightened if they trod over a corpse. In such way they slew twelve men, Rhesus 2 being the thirteenth; and having unfastened the horses whiter than snow from the chariot, they mounted and hastily returned to the Achaean camp.

Tears and laughter

Such was the end of Rhesus 2, who came to the war with decorated chariot, and ornamented armour, but for having been caught by death unawares, is remembered for all that wasted paraphernalia. Some may find his fate tragic, and had they

known the man personally, they would have probably

lamented and wept. But others, not founding

proportion between his looks and ambition, and on

the other hand, the way in which he, so suddenly,

was deprived of both life and glory, may find it

laughable. For Nemesis, they may argue, is known for reestablishing proportion, through the punishment of excessive pride. Not seldom the experiences of men, in war or in

peace, are met with either tears or laughter. And

those who weep believe themselves to be more loving

and pious, taking everything to heart, and sighing

and groaning in the company of others like them.

But those who laugh at human fate, not out of

cruelty, but for knowing that human happiness has

an end, deem it more dignified to face with a smile

what fate will anyway impose. This is their method

for reducing misery in their hearts; and for

despising tears, they believe themselves to be

wiser. In any case, with either tears or laughter, few escape amazement. And certainly not Hippocoon 1 and the other Thracians. For they were amazed beyond measure when they discovered the hideous carnage, the absence of the horses whiter than snow, and their dead king. And since amazing things may have an amazing origin, there were those who believed that the carnage had been staged by treason within the Trojan camp. But Hector 1, who had no joy in seeing his ally dead, knew that spies had killed the king, and that for him nothing could be done except burn him with splendor, thereby calming tears. As for cruel laughter, it moved to the Achaean camp, where Odysseus and Diomedes 2, after

taking a bath, had supper together, during which

they made libations to Athena, the goddess who

helped them.

Another with identical name: Rhesus 1 is one of the RIVER GODS.

|